-

- Contact Us

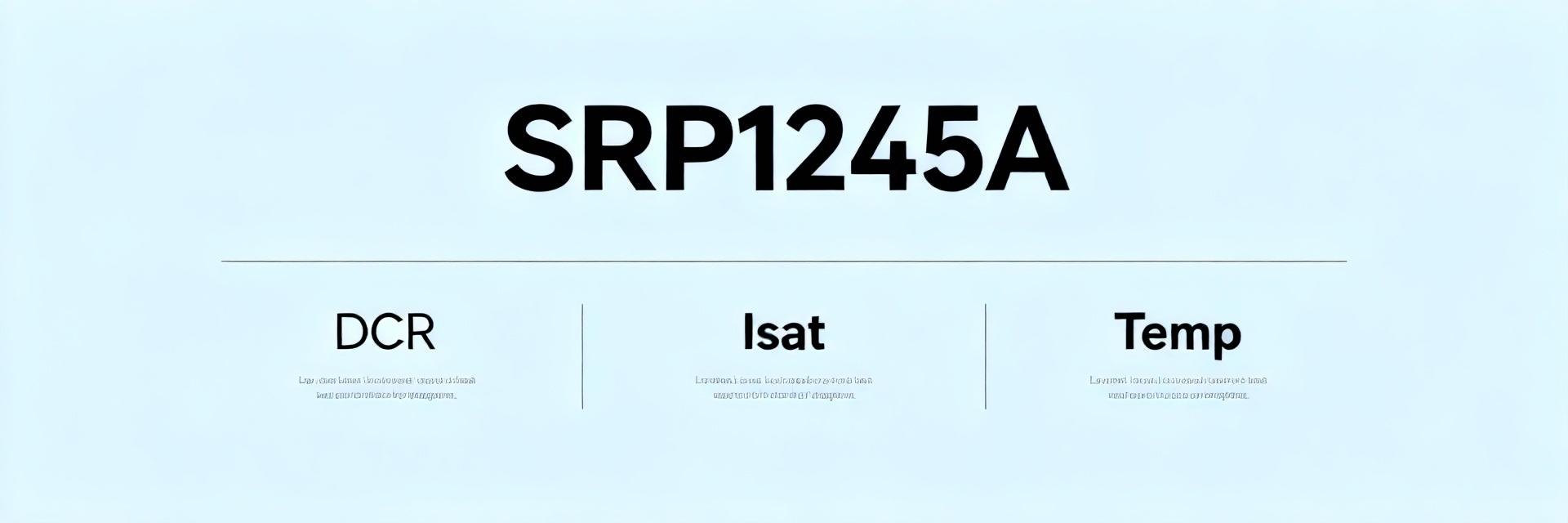

SRP1245A-180M Datasheet Deep Dive: DCR, Isat, Temp

Introduction: Point — This article teaches engineers to read the SRP1245A-180M datasheet graphs for DCR, Isat and temperature behavior and turn those numbers into concrete design decisions. Evidence — the Bourns SRP1245A family datasheet shows the typical inductance, current ratings and thermal-rise curves that define usable operating space. Explanation — by parsing the tabular specs and the plotted curves together, an engineer can predict conduction losses, estimate steady-state winding temperature, and choose appropriate derating margins so production units behave as intended. This introduction uses the part number once to establish focus and frames the practical goal: convert datasheet numbers into verified board-level outcomes.

Introduction: Point — A single stat often frames the tradeoff space: inductance vs DC bias. Evidence — the datasheet’s inductance-vs-current curve indicates a typical inductance drop at rated saturation current. Explanation — understanding that the inductance can fall roughly at the specified saturation point (commonly defined as a 20% inductance drop) lets designers compare peak currents and ripple to the inductor’s effective inductance in-circuit.

1 — Background: Where SRP1245A-180M fits and which specs matter (background)

At-a-glance datasheet summary

Point — The first step is extracting the key table entries that drive electrical and thermal behavior. Evidence — from the manufacturer’s datasheet the relevant entries are inductance (µH), tolerance, DCR (typ/max), Isat (saturation current, defined at a chosen % drop), Irms (rated rms current), temperature rise at specified currents, SRF, Q, operating temperature range and any automotive qualification such as AEC‑Q200. Explanation — these values form the quantitative basis for loss calculations, temperature estimates and margining rules. Below is a concise spec snapshot recreated from the product datasheet for quick reference (values quoted as typical datasheet entries for the 18 µH SKU):

| Parameter | Typical / Stated Value |

|---|---|

| Inductance | 18 µH (M tolerance) |

| DCR (typ / max) | ~0.08 Ω typ / ~0.12 Ω max |

| Isat (specified drop) | ~7.5 A (20% L drop spec) |

| Irms | ~5.0 A |

| Temperature rise | Datasheet curve: example ~40 °C rise @ 5 A (device on 1 in² copper) |

| SRF / Q / Operating temp | SRF several MHz / Q moderate / -40 to +125 °C |

| Automotive | AEC‑Q200 indicated for series variants |

Point — Quote constraints matter: note test conditions next to numbers. Evidence — the datasheet lists DCR at 25 °C and thermal-rise figures under a specific PCB/test-fixture condition. Explanation — when you pull numeric entries, record the test temperature, whether the inductance was measured with dc bias present, and the board conditions for thermal-rise curves; those context items change how to apply the numbers to your design.

How DCR, Isat and temperature interrelate conceptually

Point — DCR, Isat and temperature form a coupled set: conduction loss heats the part, and heating raises DCR which increases loss. Evidence — datasheet gives DCR (Ω) and separate curves for inductance vs DC current and temperature-rise vs current. Explanation — use P_loss ≈ I^2 · DCR to quantify conduction loss at steady DC, then use thermal-rise curves or approximate thermal resistance to convert power into temperature rise. Also remember that at switching frequencies, skin and proximity increase effective AC resistance, so the DC DCR underestimates switching losses. Finally, inductance drop at Isat reduces filtering effectiveness; a common datasheet convention is to call Isat the current producing ~20% inductance loss, which directly links Isat to usable inductance under load.

2 — Datasheet deep-dive: DCR (data analysis)

Reading DCR values and tolerances from the sheet

Point — Read the DCR row and capture typ/max plus test conditions. Evidence — the part’s table shows a typical DCR around 0.08 Ω with a maximum around 0.12 Ω at 25 °C in the manufacturer’s specification table. Explanation — use the maximum DCR for worst-case loss estimates unless you qualify purchased parts and can rely on typical values. Also note that DCR varies with temperature: copper’s resistivity increases roughly 0.4% per °C, so a 50 °C rise increases DCR by ~20% over the 25 °C nominal.

DCR’s impact on efficiency and thermal rise (quantify)

Point — Convert DCR to conduction loss and then to temperature rise using the datasheet curves or approximated thermal resistance. Evidence — using the typical DCR of 0.08 Ω, P_loss = I^2·DCR yields 0.72 W at 3 A, 2.0 W at 5 A, and 4.5 W at 7.5 A. Explanation — these power figures are material: 2 W of heat in a shielded SMD choke often produces a tens-of-degrees temperature rise depending on PCB copper area and thermal coupling. If the datasheet shows ~40 °C rise at 5 A and your calculated loss at 5 A is ~2.0 W, that implies an effective thermal resistance on the order of 20 °C/W for the measured fixture; use that to estimate steady-state winding temperature and compare to maximum operating limits. If switching losses are significant, add estimated AC loss to the DC conduction loss before converting to temperature.

| Current (A) | P_loss (W) | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| 3.0 | 0.72 | Low loss, minimal temp rise on good copper pours |

| 5.0 | 2.00 | Moderate loss; expect noticeable temp rise per datasheet curve |

| 7.5 | 4.50 | High loss; approaching/surpassing Isat region and high temp |

Long-tail search opportunity / related keywords

Point — Expanding section titles and captions with measurement phrases captures search intent. Evidence — phrases like “SRP1245A-180M DCR measurement” and “inductor DCR vs efficiency” map directly to common engineer queries. Explanation — include how‑to steps and worked examples with those long-tail phrases in captions and meta descriptions to improve discoverability for engineers troubleshooting losses and thermal issues.

3 — Datasheet deep-dive: Isat & inductance behavior (data analysis)

Interpreting Isat vs inductance drop curves

Point — Read the inductance-vs-DC-current plot to find the specified saturation point. Evidence — the datasheet supplies an inductance vs DC bias curve; the supplier typically defines Isat at the current giving a 20% drop from the zero-bias inductance. Explanation — identify the current where the L curve crosses 80% of the nominal inductance; that is your practical saturation point. If your converter’s peak DC bias plus ripple approaches that current, expect reduced filtering and potential control-loop impacts; pick a part with a higher Isat or redesign the current waveform to reduce dc bias.

Irms, current rating, and safety margin guidance

Point — Distinguish Isat (magnetic saturation limit) from Irms (thermal/rated current) and apply derating. Evidence — the part lists Irms around 5.0 A, while Isat is near 7.5 A by the 20% drop definition. Explanation — Isat tells you when inductance collapses; Irms tells you how much heating the part can tolerate continuously. For margin, choose Isat ≥ 1.2–1.5× peak DC in many designs and ensure Irms comfortably exceeds the expected RMS current through the winding. Example: if converter peak DC is 6 A, target Isat ≥ 7.5–9 A; if expected RMS is 4 A, a 5 A Irms rating gives a moderate margin but confirm thermal rise at planned board conditions.

How Isat choice changes topology / component selection

Point — Inductor saturation behavior affects converter topology decisions and component tradeoffs. Evidence — in buck converters with high DC bias and sizable ripple, an inductor approaching Isat will reduce filtering and increase output ripple and core loss. Explanation — when ripple current is large or transient inrush events occur, choose higher-Isat parts or parallel multiple inductors to share current and reduce both dc bias per component and per-part heating. For fast transient currents, a pulsed Isat test is more relevant than continuous Isat; ensure pulsed behavior is validated in the lab.

4 — Temperature & thermal management: reading thermal-rise and reliability data (method guide)

Using the temperature-rise vs current curves correctly

Point — Use the datasheet temperature-rise curve combined with your PCB thermal path to predict winding temperatures. Evidence — manufacturer curves typically plot °C rise versus DC current on a defined test board; the datasheet shows, for example, ~40 °C rise at 5 A in its test condition. Explanation — read the curve to get ΔT at your planned current, then add ambient temperature and any additional PCB thermal resistance. If your ambient is 50 °C and ΔT is 40 °C, winding temperature reaches ~90 °C; verify this against the inductor’s maximum operating temperature and insulation class. If the datasheet curve uses a different board/area than yours, scale the ΔT using expected thermal resistance ratios or repeat the measurement on your board.

Test conditions, derating, and AEC‑Q200 considerations

Point — Apply derating for automotive/harsh environments and observe test-condition caveats. Evidence — the product family indicates AEC‑Q200-qualified variants and an operating range commonly listed to −40 to +125 °C. Explanation — for automotive use, derate current and temperature headroom: reduce allowed Irms by an additional margin and ensure winding temps under worst-case ambient stay within the insulation and life expectations. Account for altitude, vibration and temperature cycling if AEC‑Q200 is not explicitly certified for your SKU.

Practical cooling, PCB layout and thermal mitigation tips

Point — Layout choices materially change thermal outcomes. Evidence — thermal vias, large copper pours beneath the part, and spacing to neighboring heat sources reduce hotspot temperatures and effective thermal resistance. Explanation — place the inductor over a poured copper region with multiple thermal vias to the inner and bottom layers, keep clearance from hot ICs, and maximize copper area connected to the inductor pads. If DCR-driven losses dominate, improving copper conduction lowers steady-state temperature; an example before/after: the same 2 W loss on a small pad might produce a 45 °C rise, while on a 4× larger copper area with vias the rise may fall to ~20–25 °C.

5 — From datasheet to design: measurement, verification, sourcing and checklist (method + action)

Recommended lab tests and measurement setups

Point — Validate datasheet numbers on your board and in expected operating modes. Evidence — recommended tests include precision DCR measurement with a 4‑wire ohmmeter at controlled temperature; LCR meter with DC bias (or an LCR meter + DC bias source) to measure inductance under DC current; pulsed current tests that measure inductance vs short-duration high current to determine practical Isat without overheating; and thermal imaging during steady-state to map real-board temperature rise. Explanation — pitfalls include heating during long bias tests (which changes DCR), meter limitations on low-inductance readings, and fixture-dependent thermal numbers. Use short pulses for Isat to avoid thermal drift and confirm results on the actual PCB footprint for thermal-rise verification.

Design checklist for production (sourcing and BOM)

Point — Use a concise pre-production checklist to avoid surprises. Evidence — critical checks are: confirm DCR & Isat meet loss and saturation margins; verify temperature rise on the board at planned Irms; confirm recommended footprint and reflow profile; check for AEC‑Q200 marking and RoHS/halogen-free claims; and identify alternate part numbers for supply continuity. Explanation — freeze the BOM only after lab verification on the target board; record measured DCR and inductance vs bias for the lot, and include reflow and handling notes in the assembly package to preserve electrical characteristics.

- Confirm measured DCR and inductance-under-bias meet design margins.

- Verify steady-state temperature on the target PCB at maximum expected RMS current.

- Record reflow profile and pad design; include thermal vias if needed.

- Confirm qualification claims (AEC‑Q200, RoHS) and secure second-source options.

Quick comparison: alternatives and when to swap

Point — Know when to trade lower DCR for higher Isat or vice versa. Evidence — lower DCR reduces conduction loss but often increases size or cost; higher Isat reduces saturation risk but may increase DCR or cost. Explanation — if losses dominate (efficiency-critical designs), prioritize lower DCR variants or larger footprints; if peak DC bias is the limiting factor (saturation risk), prioritize higher-Isat parts even at the cost of slightly higher DCR. Consider paralleling inductors when footprint allows to reduce both per-part DCR and dc bias per coil.

Summary

- Always read the inductance-vs-current curve to locate the effective Isat point and ensure peak DC plus ripple remains below the derated Isat for margin; this prevents unexpected inductance collapse in production.

- Compute conduction loss using P_loss = I^2·DCR with the datasheet’s max DCR for worst-case numbers, then convert to temperature rise using the datasheet curve or an estimated thermal resistance to confirm winding temperature limits.

- Derate both Isat and Irms for automotive or harsh environments, validate on your PCB using pulsed current and thermal-imaging tests, and record measured DCR/inductance for incoming inspection.

- For the SRP1245A-180M select appropriate margins: use Isat >1.2–1.5× peak DC if saturation risk exists, and verify thermal performance with your board-level copper and vias.

Frequently Asked Questions

How do I measure DCR accurately for a small power inductor?

Use a 4‑wire (Kelvin) precision ohmmeter at a controlled temperature. Before measurement, stabilize the part at the measurement temperature to avoid drift. For sub-100 mΩ DCR, use a low‑current source with high resolution or an instrument designed for low resistances; subtract fixture resistance and document the ambient temperature used for the data.

When should I use pulsed current testing to find practical Isat?

Pulsed current testing is appropriate when you need the magnetic saturation behavior without thermal biasing — short pulses (millisecond range) at currents near expected peaks let you observe inductance collapse while avoiding heating that would confound the result. Use a current probe and fast L measurement or an oscilloscope with a known stimulus to capture inductance or voltage response during pulses.

What layout changes most effectively reduce thermal rise for a high-loss inductor?

Expanding PCB copper area under the inductor and adding multiple thermal vias is the most effective and low-cost method. Increasing the copper pour area and connecting it to inner layers spreads heat; thermal vias transfer heat to other layers and the board’s bottom, reducing localized temperature. Also ensure spacing from other hot parts and consider airflow or a nearby heat sink if needed.

- Technical Features of PMIC DC-DC Switching Regulator TPS54202DDCR

- STM32F030K6T6: A High-Performance Core Component for Embedded Systems

- Tamura L34S1T2D15 Datasheet Breakdown: Key Specs & Limits

- PAL6055.700HLT Datasheet: Complete Technical Report

- FDP027N08B MOSFET Datasheet Deep-Dive: Key Specs & Test Data

- LT1074IT7: Complete Specs & Key Parameters Breakdown

- How to Verify G88MP061028 Datasheet and Specs - Checklist

- NFAQ0860L36T Datasheet: Measured IPM Performance Report

- 90T03P MOSFET: Complete Specs, Pinout & Ratings Digest

- 3386F-1-101LF Datasheet & Specs — Pinout, Ratings, Sources

-

MM74HC4050NSanyo Semiconductor/onsemiIC BUFFER NON-INVERT 6V 16DIP

MM74HC4050NSanyo Semiconductor/onsemiIC BUFFER NON-INVERT 6V 16DIP -

MM74HC4049NSanyo Semiconductor/onsemiIC BUFFER NON-INVERT 6V 16DIP

MM74HC4049NSanyo Semiconductor/onsemiIC BUFFER NON-INVERT 6V 16DIP -

MM74HC4040NSanyo Semiconductor/onsemiIC BINARY COUNTER 12-BIT 16DIP

MM74HC4040NSanyo Semiconductor/onsemiIC BINARY COUNTER 12-BIT 16DIP -

MM74HC4020NSanyo Semiconductor/onsemiIC BINARY COUNTER 14-BIT 16DIP

MM74HC4020NSanyo Semiconductor/onsemiIC BINARY COUNTER 14-BIT 16DIP -

MM74HC393NSanyo Semiconductor/onsemiIC BINARY COUNTR DL 4BIT 14MDIP

MM74HC393NSanyo Semiconductor/onsemiIC BINARY COUNTR DL 4BIT 14MDIP -

MM74HC374NSanyo Semiconductor/onsemiIC FF D-TYPE SNGL 8BIT 20DIP

MM74HC374NSanyo Semiconductor/onsemiIC FF D-TYPE SNGL 8BIT 20DIP -

MM74HC373NSanyo Semiconductor/onsemiIC D-TYPE TRANSP SGL 8:8 20DIP

MM74HC373NSanyo Semiconductor/onsemiIC D-TYPE TRANSP SGL 8:8 20DIP -

LT1213CS8Linear Technology (Analog Devices, Inc.)IC OPAMP GP 2 CIRCUIT 8SO

LT1213CS8Linear Technology (Analog Devices, Inc.)IC OPAMP GP 2 CIRCUIT 8SO -

MM74HC259NSanyo Semiconductor/onsemiIC LATCH ADDRESS 8BIT 16-DIP

MM74HC259NSanyo Semiconductor/onsemiIC LATCH ADDRESS 8BIT 16-DIP -

MM74HC251NSanyo Semiconductor/onsemiIC MULTIPLEXER 1 X 8:1 16DIP

MM74HC251NSanyo Semiconductor/onsemiIC MULTIPLEXER 1 X 8:1 16DIP