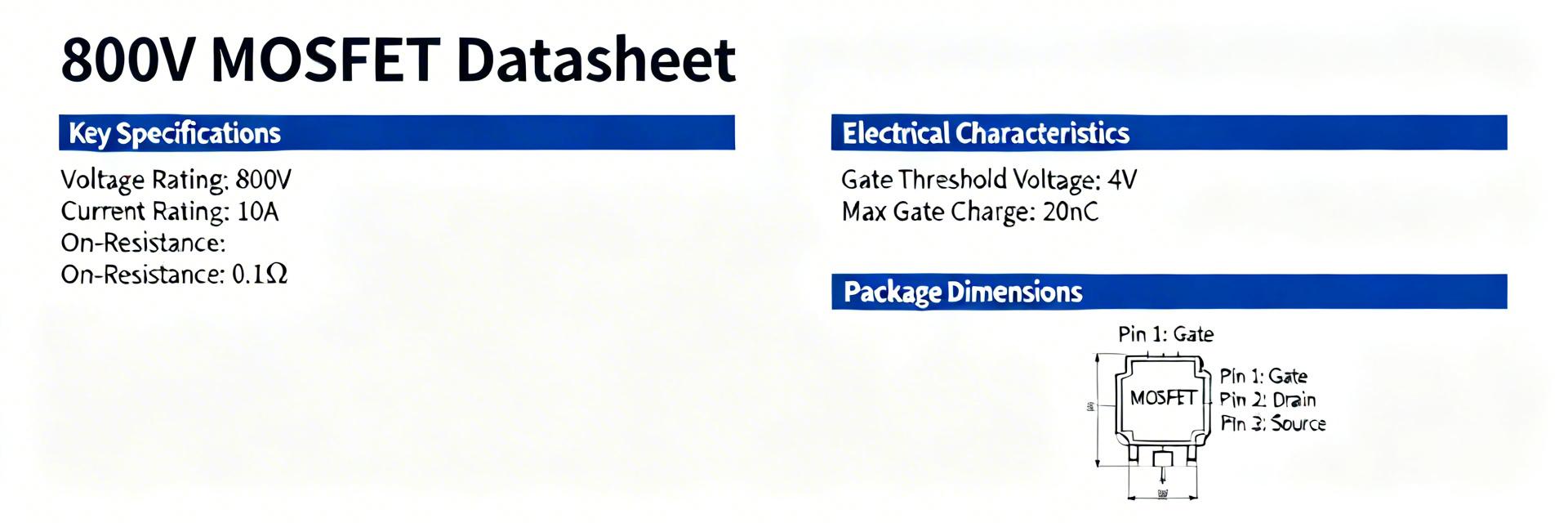

A comprehensive engineering guide to pulse power capability, thermal resistance, and safe-use design parameters. The datasheet lists pulse power capability in the kilowatt range while heatsink-mounted continuous ratings sit in the low hundreds of watts — the gap between pulse and continuous ratings determines safe use in braking, inrush limiting, and pulse-load applications. This guide walks engineers step-by-step through the datasheet numbers, shows how to convert them into voltage/current limits and temperature rise, and gives practical design checks to avoid thermal failures. WDBR3-100RKLW Datasheet at a Glance Key identifiers & what each datasheet section means Datasheets typically present part marking and package outline, a resistance and tolerance table (here: 100 Ω), continuous power ratings for a specified heatsink mounting, pulse ratings with duration/duty, thermal resistance values, and mechanical drawings showing footprint, mounting hole and lead locations. Engineers should note exactly where the resistor’s value and rated power are tabulated and any special marking that appears on the component body. Typical application contexts where these specs matter Typical uses include dynamic braking, inrush limiting, motor drives and pulse energy dumps. In such applications the distinction between continuous heatsink power and short-duration pulse power is critical: continuous ratings govern steady dissipation into a heatsink, while pulse ratings permit brief, higher-energy events provided the average power and energy per event remain within thermal limits. Interpreting the WDBR3-100RKLW Datasheet Power Specs Continuous vs. pulse power: definitions and safe-use rules Continuous (heatsink) power is the steady-state dissipation a mounted resistor can sustain without exceeding case/junction limits. Pulse (peak) power is the allowed dissipation for short durations; it depends on pulse length and duty cycle. Use P = V²/R or P = I²·R to convert between power, voltage and current. For R = 100 Ω, engineers can directly compute limits for design checks. Metric (100 Ω Resistor) Continuous (e.g., 200W) Pulse Peak (e.g., 3.5kW) Current (I) ≈ 1.41 A ≈ 5.92 A Voltage (V) ≈ 141 V ≈ 592 V Thermal Driver Heatsink θCA Internal Thermal Mass Reading power tables and pulse-rating graphs Identify charts that plot allowable pulse power versus pulse duration or energy (Joules). When a pulse-duration curve exists, read the allowed power at the intended pulse width and account for repetition rate to compute average power. If only peak power is given, estimate energy per pulse and compare with thermal capacity, or integrate P·t to a joule budget and ensure thermal recovery between pulses is sufficient. Thermal Data Breakdown: Resistance, Junction & Case Temperatures Thermal Resistance & Rise Thermal resistance (θ) links dissipated power to temperature rise: ΔT = P × θ. Typical θ terms include θJC (junction-to-case), θCA (case-to-ambient via heatsink/interface) and θJA (junction-to-ambient free-air). Sum the relevant resistances and multiply by steady power, then add ambient temperature. Datasheet Thermal Curves Use transient thermal-response curves to see how allowed dissipation falls with longer durations or higher ambient temperatures. Account for altitude and airflow: increased altitude reduces convective cooling, while forced airflow substantially lowers θCA. How to Size Heatsinks and Cooling for WDBR3-100RKLW Step 1 — Calculate Required Heatsink Thermal Resistance Choose the maximum allowable case temperature, compute allowed ΔT = Tmax_case − Tambient, then calculate required θheatsink_total = ΔT / Ptotal. Subtract interface and internal θ values from that total to find the heatsink θ. Add a safety margin (10–20%) and scale Ptotal if multiple resistors share a sink. Step 2 — Select and Validate Heatsink & Mounting • Verify mounting footprint and bolt pattern. • Choose natural vs forced convection based on ambient. • Select TIM (Thermal Interface Material) with low resistance. • Follow recommended bolt torque and clearances. Real-World Design Scenario: Braking Resistor in a Motor Drive System Spec & Verification Assume a brake event dumps 1,200 J over 2 seconds with a 5% duty cycle and ambient 40 °C. Using the resistor’s 100 Ω value and datasheet pulse limit, compute pulse power and average power, then calculate expected ΔT using summed θ terms. Size the heatsink so steady-state case temperature remains below the specified limit. Expected Failure Modes to Watch: Common failures include opens under overload, hotspot-driven degradation, and insufficient isolation. Verification should include repeated cycles until steady thermal behavior is observed. Design Checklist & Troubleshooting Commissioning Checklist Verify part number and 100 Ω resistance. Confirm heatsink mounting and TIM presence. Measure steady-state and pulse temperatures. Compare results to predicted ΔT limits. Troubleshooting Guide High Temps: Insufficient heatsink or poor TIM → Increase sink capacity. Resistance Drift: Overheating or repeated pulses → Reduce duty cycle. Intermittent Opens: Mechanical stress → Confirm bolt torque. Summary Extract resistance and rated power from the datasheet table, then convert to volts and amps using P = V²/R and P = I²·R to define electrical limits and margins. Use published thermal data and θ values to compute ΔT = P·θ; combine internal and interface resistances to size heatsink thermal resistance properly. Validate designs with steady-state and pulse testing, include safety margins (10–20%), and apply a joule-budget approach when pulse-duration graphs are absent. Frequently Asked Questions How should engineers convert datasheet power specs into voltage/current limits? Use P = V²/R or P = I²·R with the resistor’s nominal resistance to compute allowable voltages and currents for a given power. For pulse conditions, use the pulse power at the intended duration and ensure average power (accounting for duty cycle) stays below the heatsink-rated continuous power. What thermal measurements are most reliable for validating these power specs? Place thermocouples on the case near the mounting interface and on the heatsink; use IR imaging to find hotspots. Run steady-state tests for continuous power and representative pulse sequences for transients. Record temperatures until repeatable steady or cyclic behavior is observed to verify margins. When is it necessary to use multiple resistors or change topology to meet thermal limits? If single-resistor average or peak dissipation forces an impractically large heatsink, split the energy across series or parallel resistors to lower per-device dissipation. Recalculate power sharing and thermal resistance per device, and validate with the same steady-state and pulse tests to ensure even thermal distribution and safe operation.