-

- Contact Us

WDBR3-50RKLW Datasheet Deep Dive: Specs & Ratings Guide

Point: The WDBR3-50RKLW is significant for power-dissipation applications because its nominal resistance, steady-state heatsink-mounted power, pulse/peak power capability, tolerance, and temperature coefficient define safe braking and inrush handling.

Evidence: The part designation and datasheet tables list these headline numbers as critical operational constraints.

Explanation: This guide shows how to read the WDBR3-50RKLW datasheet, interpret key specs, compare continuous vs. pulse ratings, and apply the part safely in dynamic braking and inrush scenarios.

Technical Overview

Point: Readers will get a step-by-step breakdown: critical electrical specs, thermal and pulse analysis, a worked sizing example, and a practical selection and test checklist.

Evidence: Each section maps directly to typical datasheet sections so engineers can extract the required numbers quickly.

*Practitioner-focused guide for US engineers and buyers.

Pro Tip: Use the sample calculations with your measured system values rather than plugging these illustrative numbers straight into production designs.

Background & Typical Use Cases

What the WDBR3-50RKLW family is designed for

Point: This resistor family is designed primarily for high-energy dissipation use: dynamic braking, snubber/inrush suppression, load-dump absorbers, and current limiting.

Evidence: Datasheet tables typically show nominal resistance and tolerance that map directly to these use cases.

Explanation: A low-profile, heatsink-mount construction allows mounting close to system heatsinks for effective steady-state dissipation, making the family suitable where board-mounted parts cannot absorb sustained energy safely.

How form factor and mounting affect performance

Point: Single-fixing heatsink mounting and mechanical footprint drive the thermal path and electrical isolation performance.

Evidence: Datasheet mounting notes and recommended torque values govern contact thermal resistance and creepage.

Explanation: Confirm heatsink flatness, mounting torque, and required insulation/clearance before ordering; inadequate interface or wrong creepage can reduce allowable continuous power or create safety failures in high-voltage systems.

Datasheet at a Glance: WDBR3-50RKLW Key Electrical Specs

Ohms, tolerance, and temperature coefficient

Point: These define circuit accuracy and sharing behavior under temperature change. Evidence: The specs table shows nominal ohms, ±% tolerance options, and ppm/°C tempco. Explanation: For braking resistors, choose a value that yields desired dissipated energy with headroom; tighter tolerance improves predictability, while a low tempco reduces drift during long dissipations.

Rated power, derating curves & continuous vs. peak ratings

Thermal, Pulse & Reliability Ratings: WDBR3-50RKLW Deep Dive

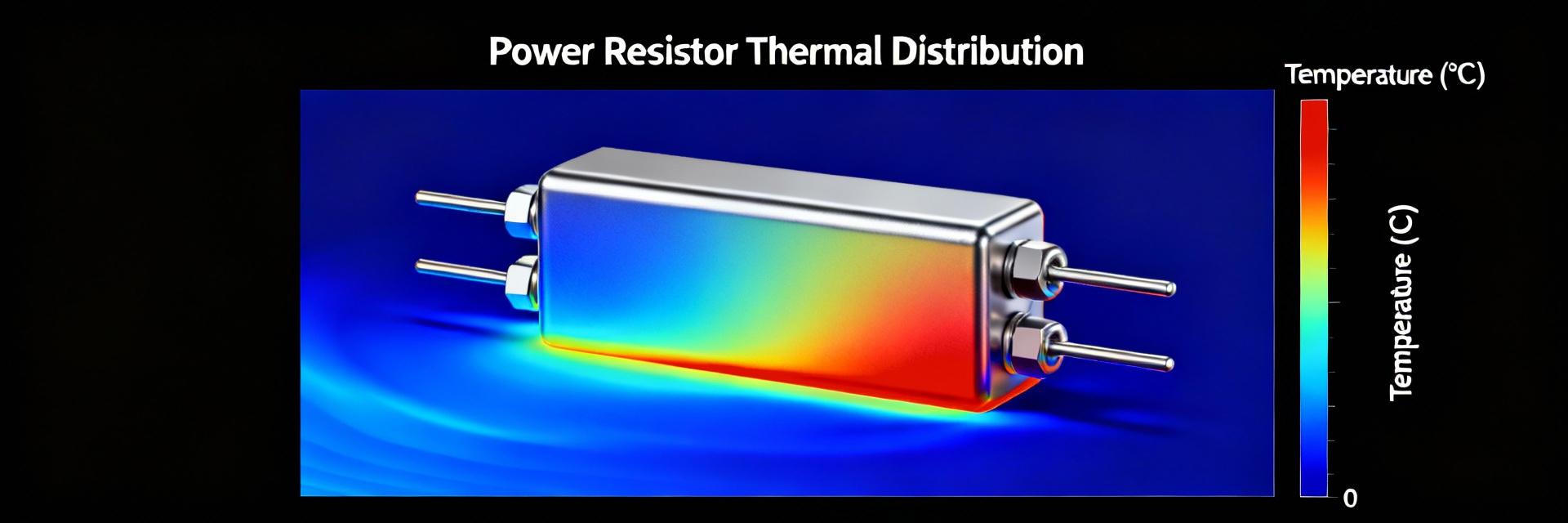

Thermal resistance and heatsink interface parameters

Tjunction = Tambient + Pdiss × (Rθ_heatsink + Rθ_interface + Rθ_part)

Explanation: Compute junction temperature using the sum of all thermal resistances; select thermal interface material (TIM) and torque to minimize interface resistance, and verify with on-board thermocouple measurements during validation.

Pulse, surge and short-duration ratings

Point: Pulse tables define the safe transient envelope. Evidence: Datasheet pulse rows list duration, repetition, and test conditions. Explanation: Translate motor energy (E = 0.5·C·V²) into equivalent pulse power over the event duration, then compare to the datasheet entry to confirm safety.

Real-World Application Example: Case Study

Sizing the WDBR3-50RKLW for Dynamic Braking

Scenario: A motor delivers 2,000 J over 2 seconds.

*Illustrative example: Always use measured system peak voltage for calculations.

Common pitfalls and mitigations

- ✘ Under-specifying heatsinks or ignoring pulse repetition intervals.

- ✔ Mitigate by adding thermal pads, forced-air cooling, and applying 20–50% headroom.

Selection & Validation Checklist

Pre-purchase Checklist

- Verify Resistance & Tolerance

- Check Steady-state Power vs Heatsink

- Confirm Mounting Hole & Torque

- Target 20-50% Safety Headroom

On-bench Validation

- Thermal Mapping (IR/Thermocouple)

- Repeated Pulse Load Testing

- Post-test Resistance Inspection

- Validate Creepage/Clearance

Summary: WDBR3-50RKLW Best Practices

- Confirm electrical fit: Extract nominal resistance, tolerance, and tempco so the WDBR3-50RKLW meets your target.

- Verify thermal adequacy: Use published Rθ values and derating curves to compute junction temperature; ensure mounting torque is correct.

- Respect pulse envelopes: Compare transient energy to pulse tables; if duty cycle is high, increase cooling or rating.

Common Questions and Answers

How do I find the nominal resistance for WDBR3-50RKLW on the datasheet? +

Point: The datasheet lists nominal resistance in the electrical characteristics table along with tolerance and tempco. Evidence: Look under the “Resistance” row. Explanation: Use that nominal value for initial circuit calculations, then adjust for tolerance and temperature-induced drift.

What pulse ratings for WDBR3-50RKLW should I compare to my transient? +

Point: Compare your transient duration and repetition to the datasheet pulse table entries. Evidence: Datasheets specify energy or peak power for fixed durations. Explanation: Convert your energy transient into the same units and duration to ensure the part matches or exceeds it.

What test steps validate WDBR3-50RKLW selection before deployment? +

Point: Perform steady-state dissipation, repeated pulse testing, and temperature mapping. Evidence: Successful validation shows stable resistance and acceptable temperature margins. Explanation: Include post-test resistance checks, fusing, and thermal monitoring in the final system.

- Technical Features of PMIC DC-DC Switching Regulator TPS54202DDCR

- STM32F030K6T6: A High-Performance Core Component for Embedded Systems

- Tamura L34S1T2D15 Datasheet Breakdown: Key Specs & Limits

- PAL6055.700HLT Datasheet: Complete Technical Report

- FDP027N08B MOSFET Datasheet Deep-Dive: Key Specs & Test Data

- LT1074IT7: Complete Specs & Key Parameters Breakdown

- How to Verify G88MP061028 Datasheet and Specs - Checklist

- NFAQ0860L36T Datasheet: Measured IPM Performance Report

- 90T03P MOSFET: Complete Specs, Pinout & Ratings Digest

- 3386F-1-101LF Datasheet & Specs — Pinout, Ratings, Sources

-

MM74HC4050NSanyo Semiconductor/onsemiIC BUFFER NON-INVERT 6V 16DIP

MM74HC4050NSanyo Semiconductor/onsemiIC BUFFER NON-INVERT 6V 16DIP -

MM74HC4049NSanyo Semiconductor/onsemiIC BUFFER NON-INVERT 6V 16DIP

MM74HC4049NSanyo Semiconductor/onsemiIC BUFFER NON-INVERT 6V 16DIP -

MM74HC4040NSanyo Semiconductor/onsemiIC BINARY COUNTER 12-BIT 16DIP

MM74HC4040NSanyo Semiconductor/onsemiIC BINARY COUNTER 12-BIT 16DIP -

MM74HC4020NSanyo Semiconductor/onsemiIC BINARY COUNTER 14-BIT 16DIP

MM74HC4020NSanyo Semiconductor/onsemiIC BINARY COUNTER 14-BIT 16DIP -

MM74HC393NSanyo Semiconductor/onsemiIC BINARY COUNTR DL 4BIT 14MDIP

MM74HC393NSanyo Semiconductor/onsemiIC BINARY COUNTR DL 4BIT 14MDIP -

MM74HC374NSanyo Semiconductor/onsemiIC FF D-TYPE SNGL 8BIT 20DIP

MM74HC374NSanyo Semiconductor/onsemiIC FF D-TYPE SNGL 8BIT 20DIP -

MM74HC373NSanyo Semiconductor/onsemiIC D-TYPE TRANSP SGL 8:8 20DIP

MM74HC373NSanyo Semiconductor/onsemiIC D-TYPE TRANSP SGL 8:8 20DIP -

LT1213CS8Linear Technology (Analog Devices, Inc.)IC OPAMP GP 2 CIRCUIT 8SO

LT1213CS8Linear Technology (Analog Devices, Inc.)IC OPAMP GP 2 CIRCUIT 8SO -

MM74HC259NSanyo Semiconductor/onsemiIC LATCH ADDRESS 8BIT 16-DIP

MM74HC259NSanyo Semiconductor/onsemiIC LATCH ADDRESS 8BIT 16-DIP -

MM74HC251NSanyo Semiconductor/onsemiIC MULTIPLEXER 1 X 8:1 16DIP

MM74HC251NSanyo Semiconductor/onsemiIC MULTIPLEXER 1 X 8:1 16DIP