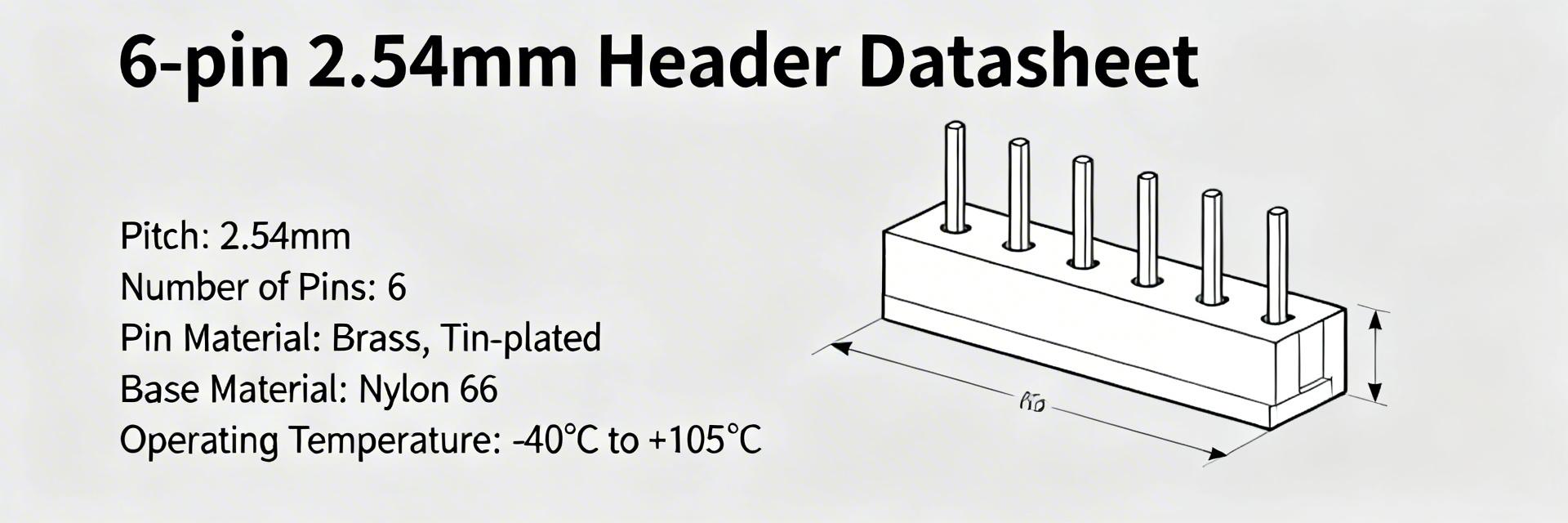

Key Takeaways Standard 2.54mm pitch ensures universal PCB compatibility. Gold-over-nickel plating maximizes long-term contact reliability. High-temp LCP housing supports lead-free reflow soldering processes. Compact 6-pin layout optimizes signal density in tight spaces. Standard 2.54 mm pitch, 6‑position headers remain one of the most common interconnects on consumer and industrial PCBs. Accurate interpretation of the 5-146280-6 datasheet prevents footprint errors, assembly rework, and failed compatibility checks. Engineers who verify key mechanical callouts and electrical ratings up front reduce first‑article failures and signal integrity issues during system integration. 2.54mm (0.1") Pitch Ensures 100% compatibility with standard jumper blocks and breadboards. Gold Plating Reduces contact resistance and prevents oxidation in humid environments. LCP Housing Withstands peak reflow temps of 260°C without deformation. This guide walks through the datasheet items that matter most—quick specs, pinout conventions, electrical and mechanical limits, material choices, assembly best practices, and procurement/test checklists—so teams can validate designs efficiently before releasing boards to manufacture. 5-146280-6 at a glance — key specs and common uses Quick specification snapshot Point: A concise spec table speeds design checks and aligns procurement and CAD teams. Evidence: Typical datasheet summaries list positions, pitch, mounting type, plating, and housing cues. Explanation: Use the table below on the PCB data sheet or BOM to avoid misreads during footprint creation. Parameter Typical Value / Note Part5-146280-6 Positions6 Pitch2.54 mm (0.1") Row count / OrientationSingle row, vertical, through‑hole Contact platingGold over nickel (select variants) HousingTypical LCP or high‑temp thermoplastic; dark color cues Differentiation: 5-146280-6 vs. Generic Alternatives Feature 5-146280-6 (Premium Gold) Generic Tin Header Advantage Contact Life Up to 100+ cycles ~25 cycles 4x Durability Heat Resistance High (LCP) Medium (PBT/Nylon) Reflow Ready Oxidation Near-Zero Moderate to High Signal Integrity Typical applications and why this part is chosen Point: The 6‑position 2.54 mm header is widely used for board‑to‑board mating, programming headers, and low‑power signal breakout. Evidence: Designers select it for robust mechanical retention, ease of hand‑assembly, and standard pitch compatibility with shrouded housings and jumper blocks. Explanation: For prototypes and production, the trade‑off is cost versus plating: gold improves contact reliability for handheld mating cycles; tin is cheaper for permanent soldered joints. When documenting selection, note expected current per pin and intended mating cycles. ENGINEER INSIGHT "When designing the PCB layout for the 5-146280-6, always prioritize the annular ring width. For through-hole headers, I recommend a minimum ring of 0.25mm to ensure mechanical stability during repeated mating cycles. Also, avoid placing sensitive high-speed traces directly under the header body to prevent capacitive coupling from the pins." — Dr. Alistair Vance, Senior Hardware Architect Pinout & electrical characteristics for 5-146280-6 Pin numbering, diagram guidance & signal assignments Point: Consistent pin numbering prevents wiring errors during assembly and test. Evidence: Datasheet drawings normally show top‑view numbering with pin 1 indicated by a chamfer or marker; mirrored bottom views are common pitfalls. Explanation: Adopt a top‑view convention in schematics and BOMs, label silkscreen with pin‑1 marker, and include a pinout diagram image (alt text: "5-146280-6 pinout diagram") on the drawing page to reduce misinterpretation. Typical Programming Header Setup Commonly used for JTAG or SWD debugging interfaces. Use Pin 1 for VCC and Pin 6 for GND to establish a standard orientation reference. 1 6 Hand-drawn illustration, not an exact schematic Electrical ratings and test conditions Point: Published ratings define safe operating envelopes and verification criteria. Evidence: Typical datasheet entries report rated current per contact, contact resistance, insulation resistance, and dielectric withstand voltage under specified test temperatures. Explanation: Designers should treat "max" values as absolute limits and "typical" values as baseline; apply derating for higher ambient temperatures and prolonged mating cycles. For validation, measure contact resistance on sample production units and compare to datasheet test method notes. Mechanical dimensions, tolerances & drawing interpretation Critical dimensions and footprint reference Point: Misreading hole size, pin diameter, or body height is a frequent cause of assembly rejects. Evidence: Datasheets list pin spacing (2.54 mm), recommended PCB hole size, pin diameter, and body height with tolerances. Explanation: Specify PCB drill size with a suitable tolerance (e.g., drill +0.1 mm relative to pin plating), annular ring ≥0.25 mm, and explicit solder mask openings. Include the datasheet dimension callouts on the mechanical drawing to avoid ambiguous CAD interpretations. Variants, breakaway options and mechanical mounting notes Point: Breakaway strips and scored parts allow custom‑length headers but change handling and mounting. Evidence: Many part families provide breakaway scoring or full‑strip options; the datasheet notes scoring locations and minimum remaining material. Explanation: When using breakaway pieces, verify squareness and file any burrs; document the final height and edge clearance for placement machines and ensure assembly teams record the breakaway method in the build instructions. Materials, plating, and environmental ratings Housing and contact materials (what to expect) Point: Material choices affect thermal resistance, soldering profile, and flammability. Evidence: Typical materials listed in datasheets include LCP housings and phosphor bronze contacts; UL or similar flammability ratings and glass transition temperatures (Tg) are often specified. Explanation: Verify the housing Tg when planning wave or hand soldering and prefer higher‑Tg resins for higher reflow exposure. Contact alloy and plating (gold over nickel) directly influence mating reliability and contact life. Environmental, reliability and compliance ratings Point: Environmental specs guide QA testing and long‑term reliability expectations. Evidence: Datasheet sections commonly list temperature range, mate cycles, humidity/thermal cycle endurance, and RoHS/lead‑free compliance. Explanation: Record plating integrity tests and cyclic humidity checks as part of qualification; plan sample sizes for contact endurance testing aligned with the stated mate cycle rating. Mounting, soldering & PCB assembly best practices Through-hole soldering and expected solder fillet standards Point: Proper fillet formation ensures mechanical strength and reliable electrical contact. Evidence: Datasheet soldering notes and IPC visual acceptance criteria indicate acceptable fillet height and wetting. Explanation: For through‑hole wave soldering, follow recommended preheat and flux guidelines; for manual soldering, aim for smooth concave fillets and avoid solder wicking up the leg which weakens mechanical retention. PCB footprint, drill & placement notes Point: Drill size, annular ring, and centroid coordinates are critical for DFM and placement. Evidence: Datasheet footprint recommendations list recommended drill and pad sizes plus tolerances. Explanation: Include centroid and orientation markers for pick‑and‑place processes when using breakaway parts; run DFM checks to verify solder mask clearance and mechanical keep‑outs prior to fabrication release. Procurement, compatibility & testing checklist Mating compatibility, alternatives and BOM notes Point: Verifying mating parts early reduces last‑minute cross‑reference work. Evidence: Datasheets specify mating heights, mating forces, and recommended counterpart receptacles. Explanation: Cross‑reference acceptable alternates by mechanical dimensions and contact plating; document acceptable alternates on the BOM with critical mechanical verification criteria to simplify procurement decisions. Inspection, test and validation checklist Point: A short pre‑production checklist catches common failure modes before fabrication. Evidence: Effective checklists include visual inspection, continuity/pin mapping, pull/push tests, and contact resistance spot checks. Explanation: Define acceptance criteria (e.g., continuity, contact resistance ≤ datasheet max, mechanical retention force within tolerance) and sample sizes for first‑article inspection to ensure consistent quality on production runs. Summary Verify pinout orientation, footprint dimensions, and material/plating choices early to avoid assembly rework. Use the 5-146280-6 datasheet as the single source of truth for electrical ratings and mechanical callouts, apply derating for thermal and long‑term use, and run the pre‑production inspection and contact tests outlined above. Document acceptable alternates and include clear pinout diagrams with your CAD and BOM for manufacturing handoff. SEO & publishing notes Primary keyword: 5-146280-6 Datasheet, 5-146280-6 Pinout. Meta description: Detailed 5-146280-6 datasheet guide covering pinout, LCP material specs, gold plating benefits, and PCB footprint design tips for engineers. Image Alt Text: "5-146280-6 pinout diagram", "5-146280-6 mechanical dimensions", "6-pin header PCB footprint".